Did you know adjustable settings on your guitar may be preventing you from playing better? It may not be your hands’ fault that you can’t play through that solo fluidly enough. With some minor technical tweaking and free time you can make your average guitar feel like an extremely expensive model.

The steps in getting a guitar to that level vary of course. There are a multitude of factors that come into play.

- How level are the frets

- String gauge being used

- What’s the scale of the guitar

- What kind of frets

- Is the truss rod working effectively

- What’s the fingerboard radius

- What is the playing style of the owner

- Do they have a light fretting hand

- Do they have a heavy picking technique

- Is the nut cut properly

- Is the neck angle too steep or too shallow

The list goes on…

For this article, let’s say the guitar is an off the shelf model with level frets. Most won’t have frets in that condition no matter the manufacturer, especially the lower end beginner models. Getting a guitar to play its best requires a fret level and crowning. A fret leveling is almost always needed unless we are talking high end guitars. Even then, I’ve had boutique guitars that needed a fret level.

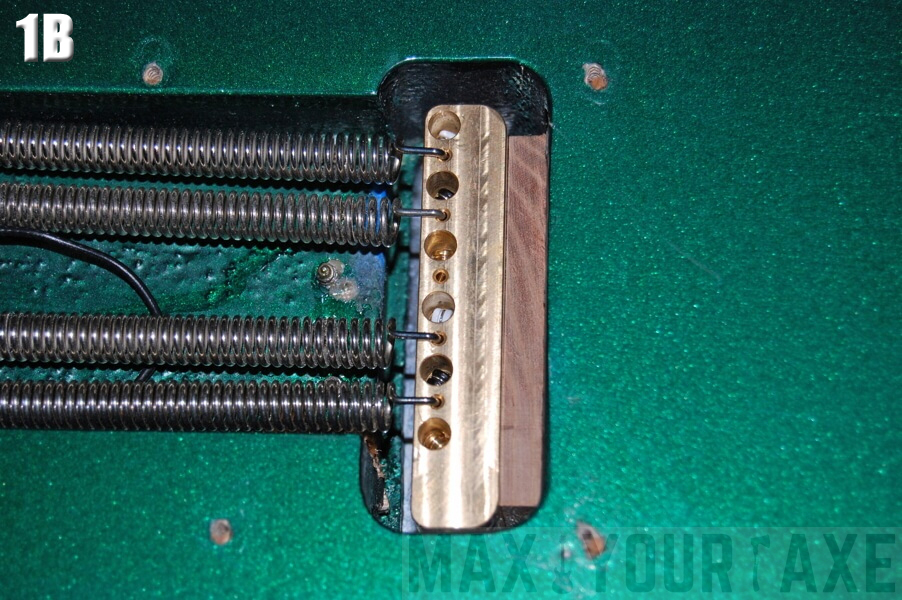

For the sake of our sanity and the length of this article, we will assume that we are good to go as far as fret levelness is concerned. I’ll post another article on that in the future because it really deserves its own separate space…it’s a lot. Another thing to note about this article is that these steps are for guitars that have a blocked tremolo or no tremolo. See FIG. 1 and 1B.

Blocking the tremolo

If using the block of wood technique, you need to loosen the tremolo screws a bit. One and a half turns from their stopping point should do the trick. This gives you a little more space behind the tremolo block to insert the wood. You should not loosen the screws too much. It creates too large a gap and when you try and screw the bridge back down you will run into an issue. The bridge will either stop short of flush or you will damage the body. See warning below.

You can block the tremolo by screwing the claw with 4 or 5 springs attached to the tremolo block. You should use five springs for string gauges 11 and above. Screw those claw screws as far as you feel they can go. Use screw wax to avoid a screw breaking off inside the body and the screws should be high quality. Do not try this with cheap import screws, they will eventually break and then it’s a major problem. If you can get the stainless screws from Callaham Guitars get them, they are worth it. You also can block the tremolo with a literal block of wood.

There are no pre-made blocks that fit every tremolo cavity. You need to make one yourself. The wooden block is placed behind the steel block (as shown in Fig. 1B above) stopping the tremolo from raising under string tension

WARNING… There is a potential caveat to using the wooden block. When placing the block into the back of the tremolo cavity it should only be slightly snug. You should be able to pull it out with your hands. The reason is this, if it is really tight when you get to the point where you are screwing the tremolo screws down, the tremolo block has a tendency to squeeze the wooden block a bit, holding it in place firmly. If it is too firm to start, when you screw down the tremolo to get it level with the body you risk cracking the wood by the screw posts.

Use a soft wood like Basswood or alder for the block, it’s more forgiving than maple or rosewood.

After you have chosen your blocking method, you need to recheck the tremolo screws. You will either have a two point or a 6 point tremolo. Tighten the screws (either 2 or 6) down so the bridge is flat on the body as seen in Fig. 1A. Do not over tighten these screws. If you used a block stop when the bridge is flush to the body. If you screw down the bridge too much without a block it will raise the back of the bridge off the body and cause tuning issues. Screw them down just enough to get the entire bridge level on the body. The tremolo / bridge should look like this when finished…

The Preliminaries

With that out of the way we need to talk about a preliminary set up. You can skip this entire prelim if you have a guitar that plays ok but just want to get it into its optimal playing shape.

If your saddles are at a good height, and your neck and strings are aligned properly, there is no need to really do what is outlined below. You may want to just read through the steps here because there are a few good pieces of info that you may find useful even if you don’t plan on going through the entire pre-set up process. This is just a cursory set up that will only serve to make sure all parts are aligned correctly. On a set neck guitar like a Les Paul this is less of an issue (hopefully).

Make sure the guitar has the gauge strings you intend to play once the set up is complete. Tune the guitar paying attention to the neck relief. To check, capo the first fret and depress the g string at the 17th fret. Look underneath the g string and see if there is any space between the string bottom and the fret tops see (Fig. 2). You should see no space or just the smallest bit, even less than what is shown in Fig. 2. The space under the strings (relief) will get larger and larger as you tune up. We don’t want this. We want the neck straight. You will need to detune and adjust the rod to ensure we arrive dead straight or with only a bit of relief under full tension. It may take a few tries but it is crucial that we get this right.

Do not adjust the rod under tension, ever. Once you have the guitar tuned to pitch with a straight neck we are focusing our attention at the bridge area. How high are the saddles and what is the action at the 12th fret? If your saddles are relatively high and the action is low (rarely the case) then the neck angle is off and we would need to introduce a negative neck angle with a shim. This is almost never the case, but I have seen it when mating different parts from different manufacturers to make a “frankenstrat” or a “partscaster”. I actually have a few where this is the case (Warmoth neck on a 60’S reissue Fender strat body). The neck sits way too high and you have to max the saddles to get the action playable.

However, the opposite is often true. Where the neck sits too low or the angle is too shallow and you have to “deck the bridge”. Meaning all saddles are so low that the adjustment screws are popping out the top of the saddles and grinding away your flesh when you play (see Fig. 4). Saddles that are too low prevent a good break angle for the string over the saddle. I find that a guitar with low saddles plays much stiffer than a guitar with high saddles, even outrageously high saddles feel better than saddles that are too low. Your mileage may vary. If you find this to be the case with your bolt on, it can be resolved pretty easily. If it’s a set neck or neck through you’re in for a major repair or at the very least a bridge replacement that may pull things into spec.

Prelims continued

For now, I’ll explain the more common neck issue. One that has a shallow angle, causing low saddles and high action. This issue is often found on lower end bolt-on models. It’s a pretty common issue, but once you can remedy this on a bolt on you can solve the opposite (too much neck angle) by doing the exact opposite. If you find the neck to be too shallow you need to introduce a shim (see Fig. 5). Most manufacturers use a piece of PSA sandpaper and stick it on the back of the heel of the neck. This works, but it isn’t the best way to solve the issue. The sandpaper trick will eventually lead to the neck past the 17th fret having a slight hump. This will cause fretting out in the upper registers.

A full size shim with a .25 or a .50 degree angle is the best bet. .25 degrees will almost always get you there but once in a while a .50 is needed. If the guitar is really bad you may need a 1 degree shim but I’ve only seen this necessary on a mixed parts Jazz Bass. The shims are available at Stew Mac. There are other various sources but I’ve never used them so I can’t comment on their quality. If you end up going the Stew Mac route get a bunch. Mostly .25 and maybe one or two .50 just in case. There are different sizes for bass and guitar so take note of that if you intend to purchase. Once you have the shim, all that needs to be done is unscrew the neck. Seems easy, it is, if done correctly.

Almost every video you will see has the guitar facing down on a table and someone with a power tool unscrewing the neck. Please don’t do this. It’s the easiest way to demonstrate the process in a video but is less than optimal in terms of keeping the neck and the neck pocket in good shape. The best way to do this neck removal is to take off all strings. Then, in the sitting position, hold the neck by the base along with the heel of the guitar (see Fig. 6). The headstock should be pointing straight up. Unscrew each screw just a tad in the beginning so as to not exert too much pressure on any one corner of the neck plate. Holding the neck and the heel keeps the neck from popping out of place when it is being unscrewed.

Once you get the screws all the way out you can separate the neck from the body. Often they just come apart. In some cases, more-so on higher end guitars the neck is fitted pretty tightly. Some so tight that you could hold the whole guitar up without the screws engaged and it won’t budge. DO NOT TRY THIS. If this is the case things can go south fast. Mostly in the form of paint chips around the top of the neck pocket area. As the neck is pulled from the pocket the friction catches the paint or the clearcoat and some may chip off. If you feel this is the case with your guitar, STOP, take it to a tech. If your neck comes off easy then you can continue on to the next step.

The next step concerns the neck pocket holes in the body of the guitar (see Fig. 7). Very often those holes are threaded. You can’t just pull the screw out, but rather you have to unscrew it out of the body. This is not optimal for the body and neck to make great contact. The holes in the body should be reamed out so the screws used to bolt on the neck can be pushed or pulled out freely with one’s hand. This is a delicate process that should be done slowly. Don’t enlarge the holes so much that the screw is floating around in there. Do this with a round file and a ton of patience. Go slow, check and recheck as you go. Once the screw is easy to push in and out we can get on with things.

Once you have those holes reamed properly, place the shim with the thicker end toward the back of the neck pocket (see Fig. 5 again). Place the neck back in the pocket making sure the shim is as far back as it can go. You may have to trim or sand the sides of the shim for a perfect fit. Screw the neck back on but do not over tighten. The screws should be sufficiently tight.

WARNING!!!

For bolt on necks with 22 frets or more, there is a fretboard extension that overlaps the pickguard. Under no circumstance should this extension be making contact with the pickguard. This is extremely important. If it is in contact with the pickguard the neck is almost assuredly not making full contact with the neck pocket. In this case you have raised the neck angle but not quiet enough. You are most likely going to cause a raised tongue, where the frets from 17th to the end of the fretboard slope upward causing buzz.

When you bolt on the neck at full screw tension you should be able to slip a piece of paper underneath that fret extension. At least a piece of paper if not two should slide underneath the extension from one side to the other feely, without it getting caught or bound between the pickguard and the fret extension. It should look very similar to Fig. 8. Anyway, if you don’t have an issue with your fret extension being in contact with the pickguard then you are ok to continue. If you do, you may need to add another shim. There is no need to continue on if that fret extension is bound up against the pickguard, it’s that big of an issue and must be rectified.

After you are sure the fret extension is not an issue, restring and tune to pitch. You will now find that you need to raise the saddles. Detune a bit and raise them. If you raise the saddles to get the action at the 12th fret in a ballpark range (4/64th or so) and the saddles are at a comfortable height you can stop, If not, add another shim by following the steps above. If for some reason the shim added too much angle and the saddles are too high (unlikely) you can take the shim and sand it slightly to make the .25 degree angle a .15 degree or so angle (it’s a little tricky to do but I’ll explain at some point in the future) and you should be good to go.

Not done yet….

After you install the shim and tune the guitar to pitch, hold the guitar in the same position as you did when removing the neck (Fig. 6). Hold the neck and the heel and with a screwdriver give each screw a slight turn to the left. Don’t worry the neck will not fly off, but you will often hear and or feel the neck slide or pop farther back into the pocket. This is because of the tension of the strings. This is a little trick you can use to get the best possible contact between the neck and the body for a bolt on.

After doing this, tighten the screws back up. They shouldn’t need much but just make sure each one is snug. Turn the guitar around and if it is a strat style guitar with dot inlays notice the positioning of the D and g strings in relation to the 21st fret dot inlay. That inlay should be DEAD CENTER of those two strings (see Fig. 9). If it isn’t, the neck is not sitting in the pocket properly. (see Fig. 10). This is not a good situation and must be rectified before continuing on.

The process of aligning the neck is often too complicated to just add here so I will have to give it it’s own article. If everything on your guitar has fallen into place, or things are at least acceptable to you we are ready to really get into this.

Now the actual work begins

First and foremost (remember the frets are perfectly level and crowned, otherwise that would be the first step) we need to check the truss rod. If you have completed the pre set up instructions you already know if your rod works or not. Leave the strings on the guitar but loosen them significantly. Do not attempt to adjust the truss rod with the strings at full tension. That will eventually lead to disaster, like a stripped nut or a rod that doesn’t function as effectively as it should. You may even snap it, and in that case the neck is firewood. People do this all the time, the internet will tell you it’s ok, it isn’t, not if you give a shit about the longevity of the guitar.

Anyway, the rod should be able to get the neck into a position called back-bow. Back-bow is basically a hump in the mid section of the neck. The fingerboard isn’t straight but rather convex. An optimal playing guitar will have a neck that is dead straight or with a slight bit of relief. Dialing in the right amount is key as you will see later on. You don’t want to crank the rod, and you don’t need a lot of back-bow to start off with. If you are using a heavy gauge you may need a little more back-bow to start with but it isn’t necessary. We are doing this because if we start out straight or with relief (concave) we will only have to go back and adjust it to a greater degree when we account for string tension.

Again, do not over crank that rod. And don’t do it under tension. Is it easier to do under tension? Sometimes, but I’m not interested in easy, I’m interested in the right way, and more importantly the safe way. Truss rods are for the most part pretty sturdy but once they have failed there is no going back, at least not cheaply. If the truss rod gives the neck sufficient back-bow we can continue on to the next step. If it doesn’t there is little need to continue on. The neck would need additional work to get it to play right. Yet another article for another time.

Ok, so we have a working truss rod. String the guitar up if it isn’t already. Once strung, tune to your desired pitch. Three things are now possible. The neck is still back-bowed. The neck is perfectly straight, or the neck has some relief (good but too much might be an issue). The first two scenarios are ideal. Actually all three are ok if there isn’t too much relief. This tells you the truss rod is more than sufficient, and you can back off (loosen) it a bit when and if needed. The third scenario (neck has relief) involves loosening the strings and tightening the rod a bit more until you get the neck perfectly straight under full tension. This may take a few attempts, and it’s annoying if you have to remove the neck to access the truss rod (vintage style rods adjust at the heel).

The easiest way to know the neck is perfectly straight is to capo the first fret and depress the g string at the 17th fret. Look underneath the g string and see if there is any space between the string bottom and the fret tops. There should be none or just the smallest bit. You can tell if there is any space by tapping the frets with the string depressed at the 17th and the capo at the first. If there is a pinging sound there is some space, if it’s silent then the string is touching the fret already. A slight back-bow is not a deal breaker for the next step anyway, but you don’t want a severe one. Too severe will just cause you double work. Too much relief would likely be disastrous.

When the neck is straight or near straight we can work on the action at the bridge and the string height at the nut. Take the capo off now. Set all the strings to 1/64th at the 12th fret. I know it’s low but we are using that height as a “safety” for adjusting the nut. If you’re really apprehensive about doing this you should set the action at zero with the strings literally lying on the frets. That would almost guarantee you not going too far.

Once all strings are set to 1/64th or zero at the 12th fret we are going to the headstock area and adjusting the height of the strings at the nut. Almost every guitar, new, used, cheap or expensive will have a nut where the slots are left high. This goes almost without exception. Why? Cause it’s a pain if you go too low. Leaving the action at the nut a little high is done on purpose. It’s easier and facilitates buzz free action at the nut when strumming open strings. For some it’s a good height, it works for them, and that’s fine, but we are fine tuning things here. To get the action as slick as possible this is almost always a problem area that needs addressing.

This is probably the most tedious and nerve-racking part of the set up (besides leveling and crowning). I set the string height at the nut from 1/64th for the high e graduating to 1.5/64th for the low E (see Fig. 11) This is pretty low and should only be done on a guitar that has a player with a light touch and plays a heavier gauge string (11s or higher). You could get away with 10s as well but that’s pushing it. Again, it depends on the player. You should probably not go lower than 1/64th at the nut on any string no matter your playing style. If you make a mistake it’s possible to fill the nut slot with CA glue and baking soda and start over. That’s another story (and honestly probably another article).

This is Nuts

The short version of filing the nut slots is this. With the guitar tuned to pitch, loosen only the string you are cutting the slot for. Once loosened pull the string from the slot and get it out of the way. I usually rest it in an adjacent slot (see Fig. 12). You will need a nut file (obviously). They aren’t cheap but to really do it right you need to invest in a few. I use a gauge about .002 wider than the string width. So for an .011 String I use a .013 file. This prevents the string from binding in the nut during tuning.

The position of the file when filing is the most important aspect here. That and remember to use a light touch and go slow. You need to have a backwards angle (front of file should point down towards the headstock, NOT the fretboard)(see Fig.13). In which case the front of the file is pointing at an upward angle. You want the nut slots to slope at an angle towards the headstock. Only the very front of the nut should make contact with the string (see Fig. 14). If the file points towards the fretboard (see Fig. 15) your point of contact for the string will be somewhere near the middle of the nut, rather than right at the front where the nut meets the fingerboard. DO NOT FILE as shown in Fig. 15, it is an example of what not to do.

I like to start with the high e, but that’s just personal preference. To clarify, I would loosen just the high e. Move it out of the way. Cut the slot, and then move the string back to the slot. Tune to pitch and if I’m satisfied with the height I move on to the b string. Go slow. Double check often. When checking you need to tune that string back to pitch, or not less than a step below.. You can’t just place it back in the slot. If you do, the measurement will read high. By the time you get to 1/64th at the nut on a slack sting, you will find it to be lower (too low in most cases) than that when tuned to pitch because the string burrows deeper in the nut when tension is applied than when it’s resting in the slot slackened.

If you go too far, it turns into a nightmare. We have a safety built in here though. Remember that ridiculously low action set at the 12th fret? Well, that was done on purpose. This super low action gives you leeway at the nut because we will obviously be raising those strings during the final set up and the action at the nut will increase slightly. You may have to go back to the nut, if you set the action at zero, to file ever so slightly. If you are anal retentive like me, this will be the case. In most cases the height difference is negligible and will never be felt by the average player. Remember this is the short version of nut filing.

Once the nut is to your liking, we move to the truss rod again. Loosen the strings and turn the rod ever so slightly as to loosen it just a bit, only about 1/16th of a turn, it won’t need much more in most cases. This truss rod adjustment adds a tiny bit of relief in the neck. Tune back to pitch and capo the 1st fret. Depress the g at the 17th and look for some space underneath that string (see Fig. 2). There should be just the slightest amount. I don’t measure this personally. It should be under 1/64th at the 7-9th frets. That is usually the spot on the fretboard that ends up having the most relief. If you have a feeler gauge I’d shoot for .008 of an inch. I like as little relief as I can get away with.

I know most people are used to playing guitars that have way too much relief. Almost every guitar in a shop has too much relief. I’ve set up guitars for people and they have said wtf, why is the action so smooth all over the neck? Well, like Jack Burton says, “It’s all in the relief(lexes)”. All kidding aside, some players do prefer a bit more relief and that’s fine. It’s definitely a personal thing but I’d suggest that any new player try a guitar with as little relief as possible. A player that has been playing with max relief for decades is probably going to find a tough time adjusting to an almost dead straight neck.

Ok, so with the relief set you will find that the action at the 12th is probably no longer 1/64th. Even if you set it at zero, the strings are probably slightly raised off the fretboard now. Even with the lowering of the string height at the nut the added relief has now pushed the action up a notch… probably. There are always exceptions to the rule, especially if the string height at the nut was egregiously high.

Bridge Adjustment

All right, the string action at the nut, and the relief have been set. Now we are moving to the bridge. You will need to raise the saddles at the bridge, or the entire bridge if it is a tune-o-matic style. If it is a tune-o-matic this process is fairly simple. Loosen the strings, raise the bridge slightly more on the bass side than the treble and tune to pitch and measure. I go for about 2.5/64th for the high e and 4/64th for the low E at the 12th fret.

Fender measures at the 17th and they use a 3/64th to 4/64th range. I stick with the 2.5/64th to 4/64th at the 12 for 25.5, 24.75 and 24 inch scale lengths and it seems to work. The action can go lower. You could feasibly go 1.5/64th to 2.5/64th at the 12th but you would have to have a super light touch and play 11s or so. That low of an action feels weird to me so I don’t go that low. Of course you’re only going that low if the frets are perfectly leveled and crowned, which is assumed for this article.

If you have a Fender style guitar you will have individual saddles. Each of those saddles needs to be raised so the action matches the aforementioned heights at the 12th fret. Slacken the string a bit before trying to raise the saddle or you risk breaking the string and stripping the saddle adjustment screw. My measurements usually read 2.5, 2.5, 3, 3, 3.5, 4/64ths from high e to low E. Note, if your radius is tighter than 9.5 a 2.5/64th action for the high e at the 12th may result in fretting out when bending. You will most likely need to be around at least 3/64th at the 12th for the high e if you have a vintage radius (7.25).

Also note. It does not matter if you have a straight radius or a compound radius fretboard. Always measure the action at the 12th fret or 17th if you like. Do not try and match the bridge to the radius of the fingerboard either by slanting the saddles or using a radius gauge, it’s useless. The saddles should be straight up and down(see Fig. 16), they should not lean to one side or the other. Some people make the saddles form an arc to mimic the fretboard radius (see Fig. 17), again, don’t. This will throw off tuning, string stability and string alignment.

If you get the strings all set with the measurements above you may be good to go at this point. It’s worth rechecking the string height at the nut at this time. If it feels good to you, leave it be. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve tried to squeeze that little extra out of the action up there and ended up having to replace the nut. Let the guitar sit for a while. 24 hours or so will let it settle in. You can play it during this time but the neck may continue to move one way or the other depending on humidity, truss rod strength and overall neck stability.

Depending on your climate these measurements will wax and wane over time. If you perform this set up in the summer when it’s humid out, your neck will bow in the winter. Setting up in the winter with low humidity will cause the neck to back-bow in the summer. If you have temp and humidity stabilization it’s a non issue, but for the rest of us, especially on the east coast where humidity and temperature fluctuate wildly, more frequent adjustment will be needed to keep the guitar playing optimally. 99% of the time the truss rod will do everything you need it to to remedy this fluctuation.

Do not raise or lower the saddles to rectify a guitar that has gone out of whack that you know you set up properly and was once playing great. The neck that has moved and you need to get that relief back to where it was when you first set up the guitar. The other measurements will fall into place, or at least be very close. If you get the relief to where it was and the action is still out of line, then move to the saddles.

One trick that has worked for me is to use 11s in the summer and 10s in the winter. The tension difference is almost perfectly equivalent to the neck movement caused by the added (or lack) of humidity. It’s not the case with every guitar but even if you still have to adjust after a string change it’s less of a turn of the truss rod.

Well that about sums it up, that is if your intonation is correct. You can intonate right away with new strings but I usually wait a day or two. You play more with stretched out strings than you do with brand new ones and the intonation can float when the strings transition from new to used. It won’t move a lot but you want it to be spot on.